Marshall Tito’s artificial leg is actually a $20 basketball from K-Mart to achieve smooth relations with an eternally 78-year old Serbian neighbour.

My downstairs neighbour’s name is Steve Bonic. He is a retired carpenter and hails from what was once Yugoslavia under Marshal Tito. He left Yugoslavia many decades ago to help construct the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme in Australia.

We sometimes meet on the landing of our building.

“I’m a carpenter. I’m seventy-eight.” It’s been the preface to his every rambling tale since I came here three years ago, his age static during all this time.

Recently we met. As usual, we then went through the lamentable state of carpentry in the Australia of today, added to which were analysis of the spurious claims by Australian state and federal governments that we were in the midst of a global pandemic.

“All bullshit, mate.”

But here was the big news. Steve said that he had finally been granted an exemption by the Australian federal Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) to return to Serbia permanently, a wish he’d had for some time. He had sold his place three months into the pandemic, carefully picking the bottom of the apartment market, and leasing it back from the purchaser while the market recovered somewhat. All that time, DFAT had senselessly refused his application again and again.

I congratulated Steve on finally getting an exemption from DFAT, an unexpected turn of events, because during the pandemic, Australia has not only banned its citizens from returning, but also banned them from leaving, even if, like Steve, they promised to never-ever come back.

Unlike the German Democratic Republic last century, Australia did not install SM-70 directional anti-personnel mines at its borders, but cynics say this is because of supply-chain issues, not because of a lack of resolve on the part of DFAT.

Steve was going.

“When are you leaving?”, I asked him.

“Tomorrow. Six o’clock they pick me up for airport.”

“So soon? How are you going to get rid of all your stuff out of your apartment so quickly?”, I asked.

“The new owner he say, leave it like is. He is renting out, so he is happy”, Steve replied looking smug, as if by giving away all his household goods, he had pulled a swiftie on the new owner.

“Well”, I said, extending a hand, “if I don’t see you before you leave, all the best in Serbia and say hello to Marshall Tito for me.”

“I will salute”, giggled Steve.

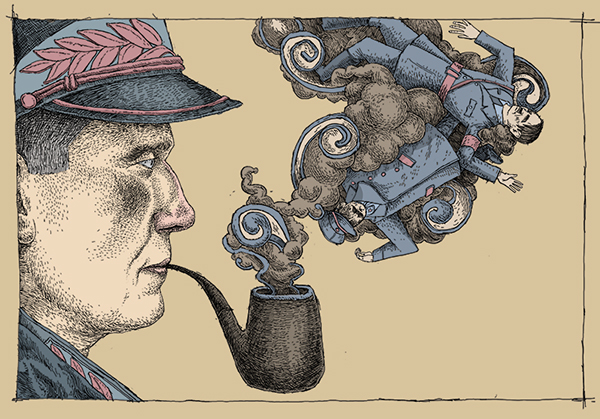

Marshall Tito had become a running gag between the two of us ever since I had bought a $20 basketball at K-Mart. It was like this.

Steve was in the habit of listening to Serbian shock-jocks on online radio stations. Shock-jocks are loud people as a rule, and their audience likes them to be even louder. So it was with Steve. In the beginning, on two consecutive evenings, I went down to knock on his door to plead for a lower volume. Each time, Steve, after opening the door to his disheveled one-bedder apartment, which smelled strongly of fried meat, had apologised profusely, offering gallantly to turn off the shock-jocks altogether. “Just turn them down, please!”, I said. He had done so, twice, but on following evenings the shock-jocks were given free reign again. I wasn’t going down a third time.

This is where the basketball comes in.

The next evening, when once again the Serbian shock-jocks reigned supreme, I bounced the ball three times. It would have been loud but did not produce the desired result. I bounced the ball three times again. No result. Clearly, sterner measures were required. So, I imagined being on court, doing a run-up to a slam-dunk. In fact, I did five or six run-ups, working up the beginnings of a sweat in my five by three metres lounge room. This did produce the desired result. The silence that followed this procedure could not have been faulted.

But I did end up doing slam-dunk run-ups every night, because Steve would never remember to start off his shock-jocks at the lower volume. I gave the ball such a workout, I even had to buy a pump to keep up its pressure and capacity for thunderous bounces.

It wasn’t until a week after the commencement of slam-dunk practice that we met on the landing, and Steve apologised for being a bad neighbour. I assured him he was not a bad neighbour, merely a loud one.

“You don’t hurt your leg?”, he asked solicitously.

The basketball routine by now being so established in my mind, I at first didn’t understand that Steve assumed I had been stamping on the floor at his shock-jocks and might have done myself an injury.

“Not my leg”, I replied when the penny had dropped and added at a complete and even to me unexpected whim, “Marshall Tito’s leg!”

Steve looked at me with wild surmise.

“Marshall Tito’s artificial leg!”, I clarified.

Marshall Tito, as readers know, developed circulation problems in his legs towards the end of his life but refused the necessary amputation of one leg, even threatening to take his own life if the doctors were to insist. His pistol was even hidden from him. Later on, he did give his consent, but by then it was too late.

“You have artificial leg of Marshall Tito?”, exclaimed Steve, disbelieving. “How you get it?”

“I got it at an auction in London in 1989”, I lied. When lying, always lie with as many unnecessary details as possible. It’s more fun that way. “Ten pounds I paid for it.”

“In London?”

“Yes, in 1989.”

“Ten pounds?”

“Ten pounds.”

He smiled broadly under his very Serbian moustache.

“Very cheap”, he said.

“A bargain”, I agreed.

“But Marshall Tito die before he can get artificial leg”, objected Steve, who had been keeping tabs on Yugoslavian politics while constructing the Snowy Hydro scheme.

“That’s probably why it ended up at a London auctioneer’s“, I replied, “his family commissioned an artificial leg for the Marshall for when he would have recovered from the amputation. When he died, they were stuck with an artificial leg for which they had no use. So, they sold it at auction.”

“So leg of Marshall Tito stamp on floor? “

“O, you know what those Croats are like! “, I said.

I then recounted to Steve the Baron Munchhausen tale about the frozen hunting horn from which no sound could be coaxed during the hunt, but which began to blow all by itself after it had been hung from a hook back at the hunting lodge, where a big fire was blazing in the hearth.

“With Marshall Tito’s artificial leg it’s similar”, I said.

Thus, a serviceable running gag was born.

“Maybe I take leg of Marshal Tito back to Serbia”, Steve said – we are now back to the chat on the landing when Steve reveals he is leaving for the airport at six in the evening on the following day.

“Sorry, no, I’m very fond of Marshall Tito’s artificial leg”, I replied.

“Yes, me too I would”, agreed Steve.

“Besides, wouldn’t the Croats want it? It might start another civil war!”

Anyway, Steve left the following day.

A couple of days later, returning from the day’s labours I noticed that the door to Steve’s apartment was open, and that people were moving about in it. I stuck my head in to introduce myself.

“I’m the new owner”, said the new owner, not shaking my hand because of COVID. He had a glazed, dazed, fazed sort of look in his eyes.

I congratulated him on his purchase.

“You know”, he said, “I told the bloke I bought it off to leave anything he couldn’t take, and I would take care of it.”

“Yes”, I said, “Steve mentioned that you had told him to just leave everything.”

“Well”, said the new owner, “that’s exactly what he did. This bloke just walked out of here and closed the door behind him.”

And indeed, it was as if Steve hadn’t left. The smell of fried meat was still there. The extension cords still spanned the ceiling.

As if time had stood still.

And on the dining room table were the remnants of what would have been Steve’s last Australian supper, a plate with much congealed fat and a couple of bones gnawed clean as well as a beer glass with some stale beer left in it. In the kitchen, further plates, cups and cutlery were piled up, awaiting a washing up.