There are two roads in and out of Western Australia. One is paved. Everything worth seeing in Western Australia is either underground or underwater. You can’t bring in fruit and veg.

The most exhilarating thing on our way from Sydney to Perth before we hit the Eyre Highway through the Nullarbor Plain happened on the way out of Broken Hill, where, in great clouds of dust, we saw two council workers, one cutting non-existent grass, the other expertly whipper-snippering imaginary grass edges. A true outback, John Maynard Keynes moment.

Broken Hill, glamorised in the movie Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and given World Heritage status, an accolade that has so far escaped hyped-up dives like Paris and Rome, has nothing going for it. It is a dump literally next to a dump of mine tailings and should be nuked. Get fridge magnet. Drive on!

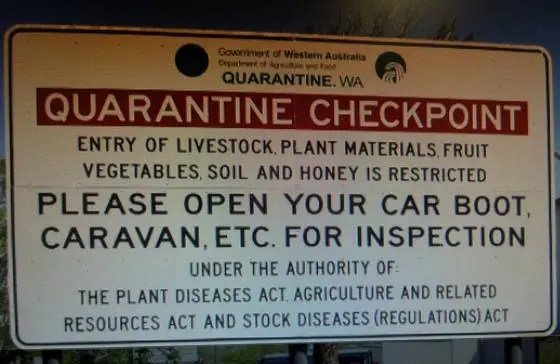

But the undisputed highlight of the crossing is going through the Western Australia fresh produce quarantine inspection.

For overseas readers, Australia is a federation of states and territories, called the Commonwealth of Australia. Australia has six states and two territories, which have their own governments. Nobody except constitutional lawyers can tell you the difference between a state and a territory. Then there is the Commonwealth, or federal, Government. Australia is mostly devoid of human settlement. It’s not quite true to say that Australia has more governments than inhabitants, but give it a bit of poetic licence and the statement flies.

One way of asserting statehood is by banning the importation of fresh produce without official permission. Queensland used to do it but gave it up after the New South Wales city of Tweed Heads effectively merged with the Queensland town of Coolangatta. Even perennially and notoriously dim-witted Queensland governments eventually realised that fresh produce quarantine requirements meant that in many places you could not cross the street eating an apple.

West Australia, where secession is a top-of-mind issue among its invariably redneck politicians, fresh produce quarantine is a conditio sine qua non. They don’t use sniffer-dogs, like Tasmania does, where they us dogs who failed blind guide dog school, flunked drug detection, but can do fruit and veg. They don’t need to. In WA they use people! They don’t sniff but are very good at their job.

There’s just the one highway going into WA, so it’s easy to stop and search travellers who have stocked up on fruit and veg in Ceduna in South Australia, just before hitting the earthly equivalent of a black hole, the Nullarbor Plain.

Apparently, most people just flatly deny carrying anything illegal, expecting the simple inspector souls to go, “Oh, alright then.”

Unfortunately, inspectors don’t wave anyone through. They first show you a sheet with banned produce and ask you whether you have “any of these items.”

When you say no, they say, “Well let’s have a look then”. And a look they have.

The car in front of us got busted for spuds, but I have to say, those people deserved to get busted. I mean, just stuffing a five-kilo bag of potatoes in a corner of your boot is a little bit too obvious. Then out came the apples, broccoli and a forlorn stick of celery. They got off with confiscation and a warning. First offence.

While the search of the car in front proceeded apace, the Institute had commenced to execute its plan, carefully prepared during the many hours of driving through utterly uninteresting landscapes.

I loitered outside our van, nonchalantly eating grapes from a Tupperware container. When an inspector moved over to us, I met him with a solicitous “Where do I put these?” He motioned wordlessly to the giant bright yellow bin three feet away from me marked “Fresh Produce Disposal Bin”. Then he produced the colourful sheet and asked, “Are you carrying any of these items, sir?”.

I carefully studied the colourful sheet and claimed we weren’t.

“Are you certain you are not carrying any of these items, sir?”

“I am certain, officer. That would be against the law, and as you saw for yourself, I voluntarily disposed of our grapes.”

“Let’s have a look, then.”

So the inspector inspected the van’s fridge and every cupboard, down to the space where the second battery sits. Nothing.

But then he found a piece of lettuce on the floor! This was an oversight on the Institute’s part. This piece of lettuce was not meant to be there. It was not part of the plan.

“What’s this?”, the inspector demanded suspiciously, holding up the offending piece of lettuce.

Mrs Henry saved the day. “Ah, that fell on the floor when we had lunch earlier.”

The inspector clearly disbelieved even this essentially true answer.

I snatched the piece of lettuce from his hand and carried it off to the yellow bin, holding it up for the occupants of cars behind us to see and understand that these inspectors were not to be trifled with. They found everything. They were relentless. They were trained sleuths.

When I got back, the inspector was still standing inside the van, casting around suspiciously. All the cupboards, spaces and cavities had been found to be clear of contraband, but he still didn’t trust it. He glanced at our suitcases, stashed in the front top part of the van. “I’ll get them down for you, officer?”, I offered.

He was about to fall for this old reverse psychology trick when he spotted it and said, “If you wouldn’t mind, sir.”

So, with a lot of huffing and puffing and exaggerated pulling, I got down the first suitcase. He opened it and looked inside. It was empty except for the 20-inch electric fan we carried because it gets hot in winter in WA. Then I got down the second suitcase, in which we had put one iceberg lettuce and a jar of honey (honey is also banned).

He opened the suitcase and looked inside, made to riffle through its contents but then said, “Alright then, sir. Thank you very much, sir.”

It just shows that those hours of mindless driving through the Nullarbor can be used fruitfully, if the Institute may allow itself that pun, to think up an exciting fruit and veg trafficking scheme to truly make crossing into WA the highlight of the journey. In this case, it came down to the last line of defence, which was to cunningly hide one iceberg lettuce and one jar of honey in a suitcase under Mrs Henry’s undies and bras.

WA quarantine inspectors are tough, but they’re not going to go through women’s underwear.